When an untreated infection leads to heart valve disease

By American Heart Association News

Much as he tried, Gabriel Oluka could never keep up with other children.

As he got older, he experienced heaviness in his chest, frequent sore throats and occasional painful joints. Sometimes his breathing became too rapid, and he couldn't always sleep lying down.

But what he remembers the most was constant exhaustion.

"Even when I was doing nothing, I would sit and feel tired," said Oluka, who grew up in a village outside of Lira, a city in northern Uganda. "I would be absent from school. I would miss a lot of things."

At the root of Oluka's health issues was something several million Americans, especially children, suffer from every year – strep throat.

Antibiotics are usually prescribed to treat strep throat. But when it goes untreated or undetected, it can lead to acute rheumatic fever. From there, it can develop into rheumatic heart disease, which seriously damages heart valves.

In Oluka's case, two of his four heart valves were no longer functioning. In 2017, he was lucky enough to connect with the Rheumatic Heart Disease Center.

Launched by Children's National Health System in Washington, D.C., the center studies prevention and treatment of the disease and is training the next generation of cardiovascular professionals. It is co-led by Dr. Craig Sable, associate division chief of cardiology at Children's National, and operates from three cities in Uganda, including Lira.

"Rheumatic heart disease is one of the world's deadliest infectious diseases," Sable said. In the U.S., it has been all but eradicated, he said. However, globally, an estimated 33.4 million people live with RHD, and about 300,000 die from it each year, according to a 2017 study. If the disease damages a heart valve enough to strain the heart, the valve may need to be replaced.

"It's really a disease of poverty," he said. "Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the disease is highly endemic, as it is in some parts of Asia and the poorer parts of India. People aren't paying attention to RHD because it is mostly happening in the poorest areas in Africa and other developing countries.

"Plus, when you see hundreds of thousands of people dying from end-stage heart disease, it doesn't easily equate to treatment of sore throats," Sable said. "It's not intuitive."

The condition can go undetected anywhere, including the U.S., where Feb. 22 is National Heart Valve Disease Awareness Day.

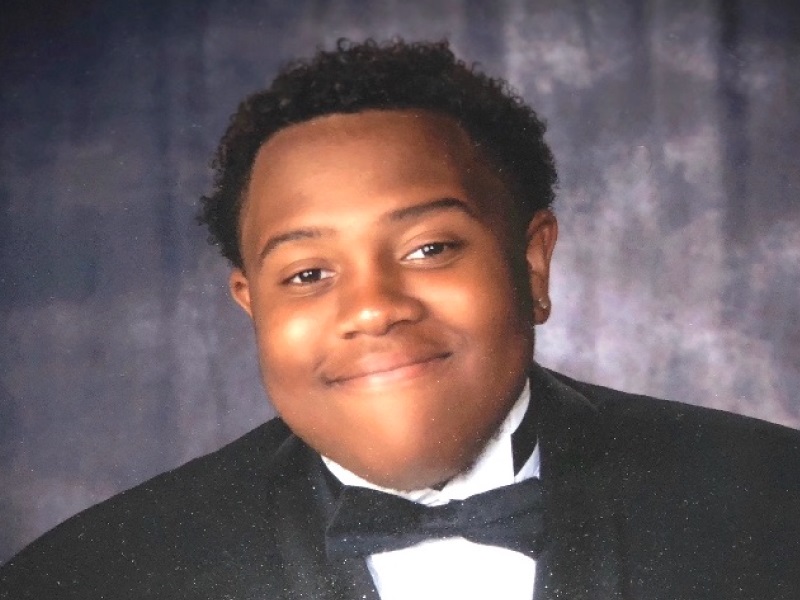

Maryland teenager Prince Pratt, whose upbringing was vastly different from Oluka's, nonetheless shared similar experiences.

Growing up, he was often winded and experienced chest pains. At 16, with collapsed lungs and breathing issues, he was rushed to Children's National, where doctors diagnosed RHD. They guessed he had undetected strep throat as an infant.

Pratt, now a 19-year-old sophomore at Towson University, said he now can do "pretty much anything anyone else can do."

Both Pratt and Oluka underwent open-heart surgery to replace damaged heart valves – Pratt at Children's National and Oluka in Uganda, with assistance from the D.C. hospital's doctors.

Sable and a group of surgeons fly to Uganda periodically to operate on children affected by RHD. While there, they promote their research efforts "to develop a vaccine, figure out why rheumatic fever isn't being diagnosed and develop population-based models to make the case to have governments invest in RHD," he said.

"There are tens of thousands of people that need heart valve surgery that are never going to get it. Plus, we've detected that almost 4% of children in Uganda have early RHD."

Oluka, now 23, feels fortunate he was among the relative few who received proper diagnosis and surgery, though he also regrets missing out on his youth and schooling. Now he's able to hang out with friends, play some soccer and help his family work their land and harvest crops.

"I'm much happier and more outgoing," Oluka said. "And my parents aren't worried all the time."

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].